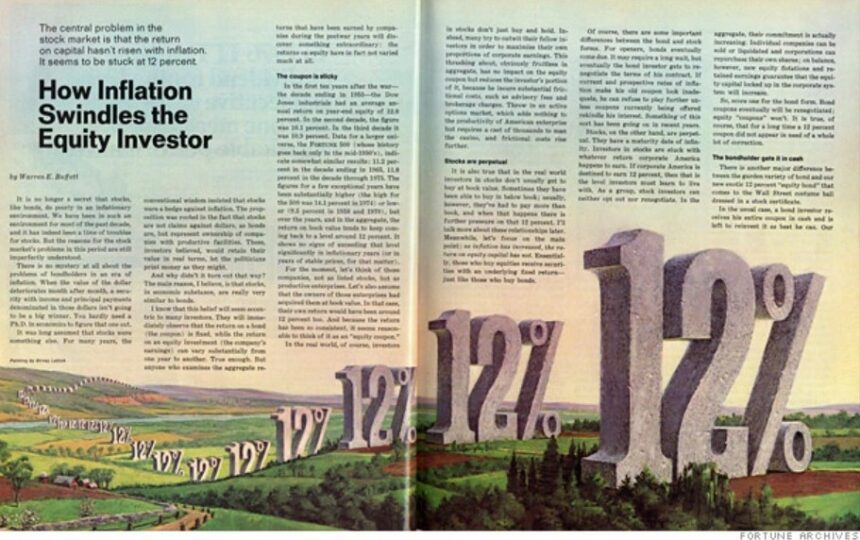

May 1977, Warren Buffett wrote on Fortune Magazine:

One of the core issues in today’s stock market is that the rate of return on capital has not kept pace with inflation, as returns seem to have stagnated at 12%.

In an inflationary environment, stocks perform poorly, much like bonds, and this is no longer a secret.

For the majority of the past 10 years, we have been in such an environment, which can be considered a dark period for stock investments. However, the reasons behind the poor performance of the stock market have yet to be fully explained.

It is well-known that bondholders in an inflationary period face troubles.

As the value of the US dollar depreciates month after month, one doesn’t need to possess a Ph.D. in economics to confidently assert that securities denominated and paid in dollars can no longer be the big winners.

However, stocks have always been seen as an exception. For many years, the conventional wisdom insisted that stocks were a hedge against inflation. But the truth tells us that stocks cannot withstand the devaluation of the dollar; they are merely representations of ownership in productive companies, just like bonds.

Investors firmly believe that while politicians may print money at their will, assets must reflect their true value.

Why wouldn’t there be different outcomes? I believe the main reason is that, in terms of their economic characteristics, stocks are actually very similar to bonds.

I understand that many investors find this concept difficult to comprehend. They may argue that bond returns (interest rates) are fixed, while the returns on equity investments (also known as company profits) show significant variations when compared year after year.

That’s absolutely correct! However, if someone were to examine all the profits companies have earned since World War II, they would discover an unusual fact—the return on net assets of companies has not changed significantly over these many years.

The Dollar Formula for Investors

In order to ensure a consistent equity return of 12%, investors may seek additional opportunities in the coming years. Achieving this is indeed possible, as many investors have successfully done so over an extended period of time. However, future returns may be influenced by three variables: the relationship between net worth and market value, tax rates, and inflation.

Let’s first focus on calculating net worth and market value. If stocks were always sold at their net worth, things would be straightforward. If a stock has a net worth of $100 and an average price of $100 , a company’s 12% profit would translate into a 12% return for investors (excluding transaction costs for now).

If the distribution ratio is 50/50, investors will receive a cash dividend of $6 , and since the company’s net worth will also increase by $6 , investors will gain an additional $6 in market value.

However, if stocks are sold at 1.5 times their net worth, the situation changes. Investors still receive a cash dividend of $6 , but in relation to the purchase cost of $150 , the dividend yield is only 4%.

In this case, the company’s net assets also increase by 6% to $106 . If the pricing remains at 1.5 times the net assets, the market value held by investors will increase by the same proportion, 6%, to $159 . Although the company’s profit remains at 12%, the total return for investors, which includes market value appreciation and dividends, is only 10%.

Conversely, if the investor’s purchase price is below the net asset value, the situation is different.

For example, if the stock price is only 80% of the net assets, under the same profit and distribution conditions, the dividend yield will reach 7.5% ($6 cash dividend / $80 stock price), and the market value appreciation will be 6%, resulting in a total return of 13.5%. In other words, in line with our intuition, we can achieve better results by purchasing at a discount rather than a premium.

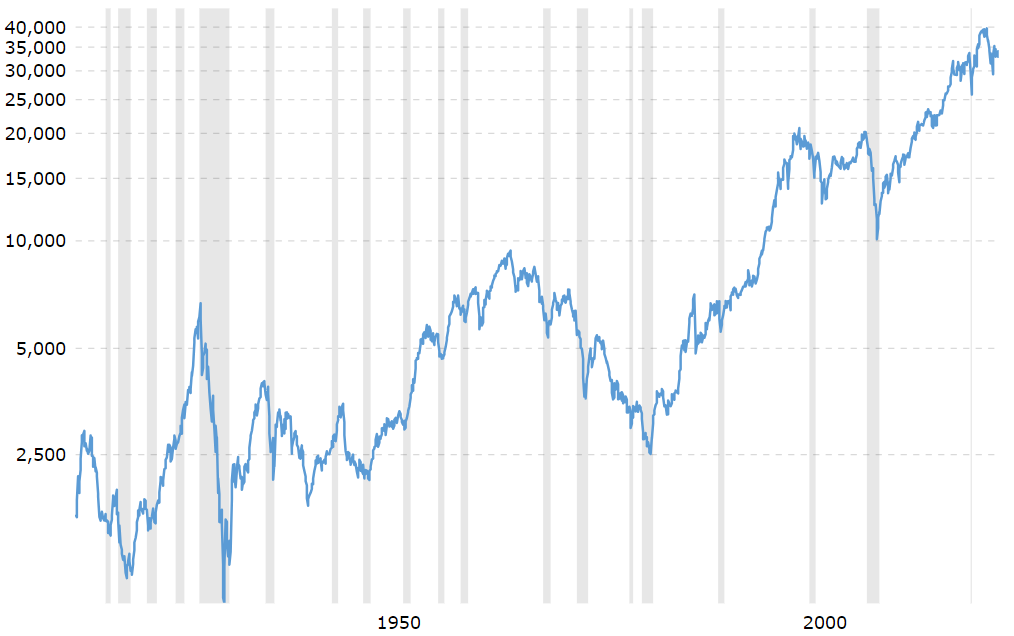

In the post-war years, the Dow Jones Industrial Average has fluctuated between a minimum market value of 80% of its net asset value (in 1974) and a maximum of 2.32 times its net asset value (in 1965). Most of the time, this ratio has exceeded 100% (as of early spring this year, the ratio was 110%).

Let’s assume that in the future, this ratio will be approximately 100%, meaning that stock investors can obtain the full 12% profit. At least, this number can be achieved on paper before considering taxes and inflation deductions.

7% Post-Tax Profit

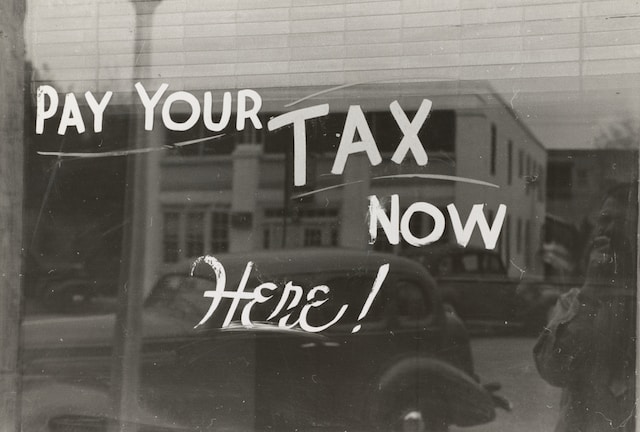

When it comes to investment returns, how much is deducted in taxes from the 12% profit? For individual investors, combining federal, state, and local taxes, it is safe to say that 50% of dividends and 30% of capital gains will be taxed. While most investors may have lower applicable tax rates, larger investors will face significantly higher tax rates.

With the introduction of new tax laws, according to reports from “Fortune” magazine, the applicable tax rate on capital gains for high-income earners can reach up to 56% in cities with high tax burdens.

Let’s make an assumption that aligns with the current situation. Out of the 12% net assets profit, 5% is distributed as cash dividends (reducing to 2.5% after tax), while 7% of the profit is retained. This retained surplus will correspondingly increase the market value of the corresponding stocks (after 30% income tax, the effective post-tax return is 4.9%), resulting in a total post-tax income of 7.4%.

Taking into account friction costs, the overall return will decrease to 7%. To provide a more precise description of our stocks and bonds theory, we can consider stocks as tax-free perpetual bonds with an interest rate of 7% for individuals.

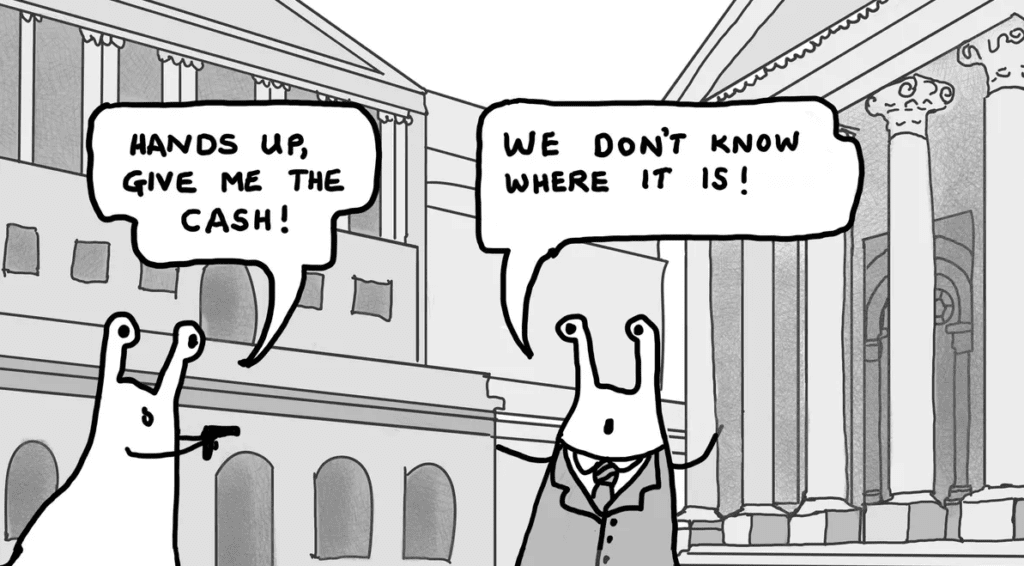

Unanswerable Question

When it comes to the crucial question of inflation rate, nobody seems to have the answer, including politicians, economists, and renowned scholars. Just a few years ago, they believed that the rising unemployment and inflation observed worldwide would be as mild as trained seals.

However, several indicators are pointing against price stability: the scope of this inflation is global, and some influential groups in our society are accustomed to diverting their energy towards shifting economic problems rather than resolving them.

Those in power might even be reluctant to tackle critical issues that have life-altering consequences, such as energy and nuclear proliferation, if they can postpone them. The current political system allows congress members who bring short-term benefits to be re-elected repeatedly, despite their decisions causing long-term suffering.

This explains why those politicians in office stubbornly oppose inflation while simultaneously contributing to its creation. (This split personality doesn’t lead to a loss of their grasp on reality; the legislators have already ensured that their pension plans are entirely different from those in the private sector. Once retired, their pension benefits fluctuate with the cost of living.)

The prevailing view is that the intricacy of financial and fiscal policies will reflect in future inflation rates. However, there are numerous variables in various inflation formulas, and each variable can influence the final outcome.

At its core, inflation during peacetime is a political problem rather than an economic one, and the key lies in human behavior rather than economic behavior. It’s self-evident what would happen if you alter politicians’ choices before the next election.

Broad-based comprehensive statistics cannot yield accurate figures. In my opinion, inflation rates are likely to hover around 7% in the coming years. I hope this prediction is wrong, but it may turn out to be right.

Predictions tell us more about the prophets themselves than the future, and you can easily substitute your own perceived inflation value into investment formulas. However, if your prediction is only 2%-3%, you’ll be seeing things differently from me.

Now, let’s summarize our findings: Pre-tax returns adjusted for inflation stand at 12%, post-tax returns adjusted for inflation are at 7%, and post-tax returns adjusted for both inflation and taxation result in zero. It doesn’t sound like a formula that would cause panic.

As an ordinary investor, you may accumulate more paper currency, but you won’t gain more purchasing power. This differs from what Benjamin Franklin said (saving a penny equals earning a penny) but aligns with Milton Friedman’s view (capital consumed by the masses is equivalent to investment).

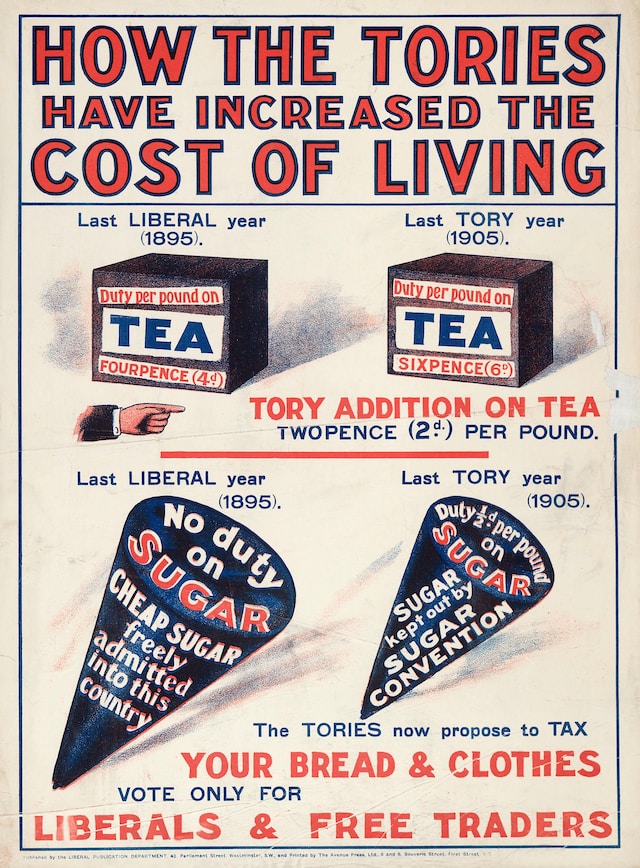

The Neglected Aspects of Widows: Understanding the Destructive Power of Inflation Tax

Inflation has a more destructive impact than the tax laws implemented by legislative bodies. It possesses an exceptional power known as the “inflation tax,” which gradually erodes capital over time. To illustrate this point, let’s consider the scenario of a widow with a bank account yielding a 5% interest rate. When there is zero inflation, she is subjected to a 100% tax on her interest income. However, if inflation stands at 5%, her interest income tax becomes zero.

Consequently, after taxation, her real income becomes zero, and every penny she spends comes directly from her capital. While the widow may be aware of the burdensome 120% income tax, she may not fully realize the impact of a 6% inflation rate, even though both factors are economically equivalent.

If my inflation estimate discrepancy is accurate, the disappointing outcome will manifest not only during market downturns but also during market upswings. For instance, last month (at the time of writing), the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) stood at 920 points, which was 55 points higher than its position ten years ago. However, when adjusted for inflation, the DJIA actually declined by 345 points, rising from 865 points to 520 points. Even with such a result, half of the profits were still retained from shareholders.

In the next ten years, considering a combination of factors including a 12% equity return, a 40% payout ratio, and a 1.1 price-to-book ratio, the Dow Jones Index is expected to double. However, if the inflation rate reaches 7%, even investors who sell their stocks at 1,800 points in the DJIA and pay capital gains tax will find themselves in a worse situation compared to today.

Regardless of the challenges that may arise in the new investment era, it is certain that investors will seek ways to achieve exceptional returns. While this desire is unlikely to be fully realized collectively, it is entirely impossible. If you believe there is a way to defeat the inflation tax through securities trading, I would gladly be your broker rather than your partner.

Even so-called tax-exempt investors, such as pension funds and university endowment funds, cannot escape the inflation tax. If my estimated annual profit of 7% only manages to compensate for the loss of purchasing power, donation funds will have no income before catching up with inflation. In an environment with 7% inflation, if the overall investment return is 8%, these presumed tax-exempt institutional investors are effectively burdened with an “income tax” of 87.5%.

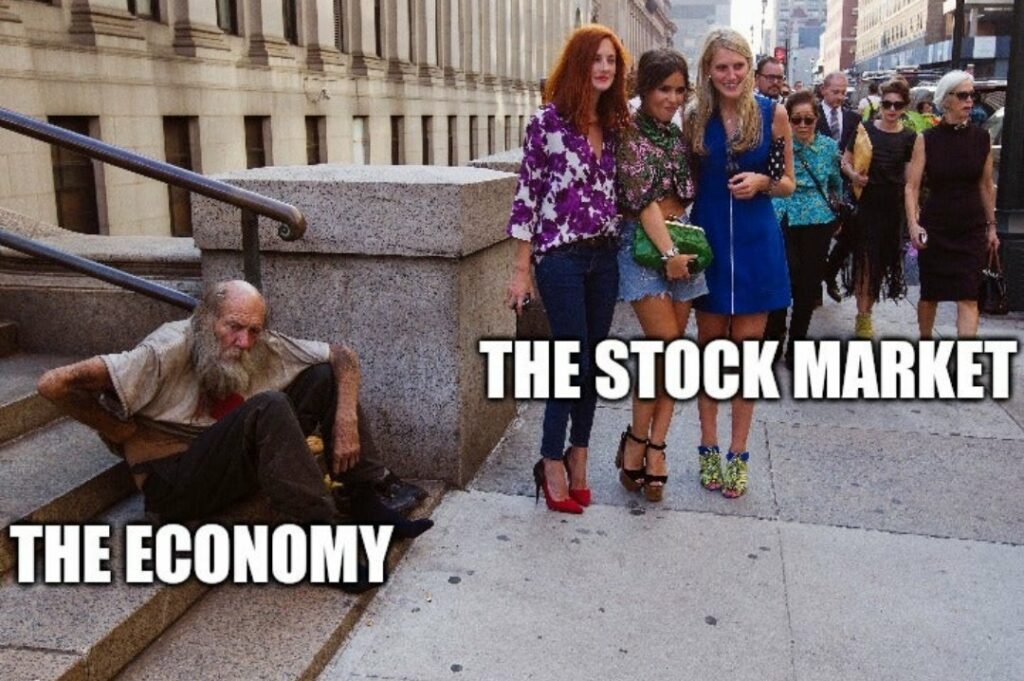

The Social Formulas

Unfortunately, the primary issues caused by high inflation are mostly directed towards society as a whole rather than individual investors. Investment income only accounts for a small portion of national income. However, if the real income per capita continues to grow at a healthy rate while investment returns remain zero, it may lead to an improvement in social equity.

In a market economy, asymmetric returns are created among participants. Those who possess talents in music, physical attributes, strength, intelligence, and other areas will have a significant amount of ownership in future national output (stocks, bonds, and other forms of capital).

The situation is similar for those who are fortunate to be born into families with substantial wealth. If real investment returns are zero, a larger proportion of national wealth would transfer from these note holders to citizens who have equivalent value and work diligently but lack “gambling” talents. In this way, it would be less likely to add an insult to this inherently equal world, risking divine punishment.

However, relying on wealthy stockholders to bear the costs and enhance worker welfare has limited potential. Currently, the total wages of employees are already 28 times the total dividends, with most of these dividends flowing into pension funds, non-profit organizations like universities, and the hands of non-wealthy individual investors.

In such an environment, if the dividends belonging to wealthy stockholders are now transformed into wages, it would resemble a one-time transaction, akin to killing the hen for its eggs. This would result in a smaller increase in actual wages in the future compared to the share we could originally obtain from economic growth.

The Impact of Inflation on Wealth and Economic Prosperity

In order to reduce the wealth of the affluent and provide even temporary assistance to the impoverished, it is not effective to impose the influence of inflation on their investment portfolios. The economic well-being of the poor fluctuates with the extent to which the entire economy is affected by inflation, and generally, this impact is negative.

Real capital invested in modern productivity brings substantial economic benefits while yielding lucrative returns. Without new capital expenditures in the entire industry, there would be no sustainable creation and employment, and the enormous demands for jobs, consumption, and ambitious government commitments would ultimately become empty promises.

The Russians are well aware of this, just like Rockefeller, which is also one of the reasons for the economic miracles in West Germany and Japan. Despite our evident advantages in energy, the high accumulation of capital has ensured that these countries far surpass us in terms of improvements in living standards.

To understand the impact of inflation on the accumulation of real capital, it is necessary to perform some calculations. Let’s go back to a net asset return rate of 12%, which is considered to be achieved after depreciation. If these factories and equipment can be repurchased in the future at prices approximating their original costs, then these profits are equivalent to the surplus obtained after the replacement of existing production capacity.

The Impact of Inflation on Profit Allocation and Real Growth

We assume that half of the profits are distributed as dividends, while the remaining 6% of equity capital returns are used for future growth. In a low inflation environment, such as 2%, most of the retained earnings can be transformed into real productivity growth.

In this scenario, to maintain this year’s production capacity, 2% of the earnings will be invested in accounts receivable, inventory, and fixed assets in the following year, while the remaining 4% of the earnings will be allocated as asset investments to increase new production capacity.

The 2% earnings are used to compensate for the depreciation of the US dollar caused by inflation, while the remaining 4% of the earnings are used to finance real growth. If the population growth rate is 1%, the actual productivity growth of 4% will translate into a 3% increase in per capita net income. This has been the general situation of our national economy in the past.

Now, let’s adjust the inflation rate to 7% and calculate how much earnings are available for investment in real growth after deducting the inflation factor. The answer is zero if the dividend policy and leverage ratio remain unchanged. After half of the profits at 12% are distributed, an equal-sized 6% of retained earnings are left, but these retained earnings are depleted by the additional capital required to maintain last year’s production capacity.

After deducting regular dividends, there are no real earnings available to finance genuine expansion. In light of this, many companies are seeking changes and asking themselves, how can they reduce or even stop dividend payments without angering shareholders? I bring them some good news: there is now a solution available.

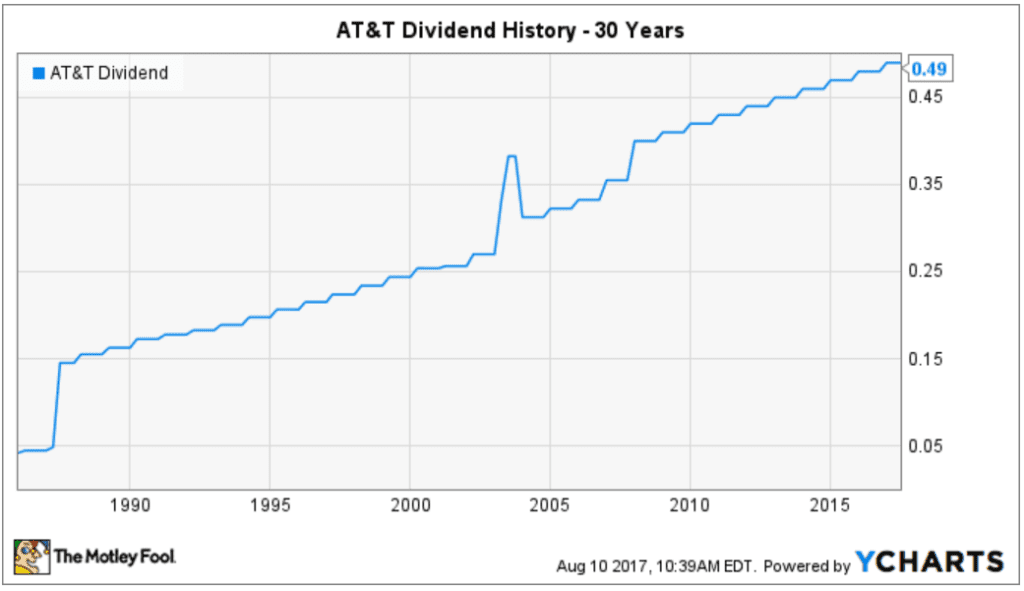

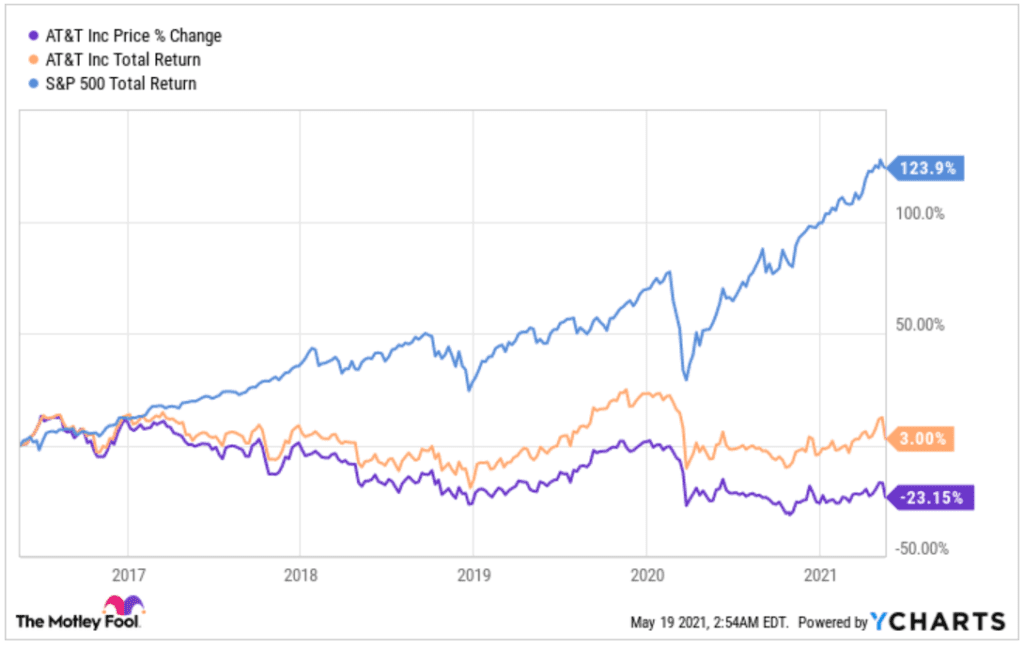

In recent years, the public utility industry has already lost the ability to pay dividends unless shareholders agree to purchase their newly issued shares. In 1975, while paying out $3.3 billion in dividends, the electric power industry requested $3.4 billion in capital from its shareholders.

Of course, the power companies implemented this technique of transferring money from one pocket to another not for show. Perhaps you remember that in 1974, power companies unwisely informed their shareholders that there was no more money available for dividends. The market gave a disastrous response to this kind of honesty.

Nowadays, smarter public utility companies continue to pay dividends and even increase quarterly dividends, but they require both new and existing shareholders to return the money. In other words, the company issues new shares. This process leads to a significant flow of capital to tax authorities and underwriters, with everyone seemingly delighted (especially the underwriters).

AT&T’s Delightful Innovations and Shareholder Benefits

Inspired by these success stories, many public utilities have come up with more convenient methods. Companies have combined dividend decisions, shareholder taxation, and stock issuance without actual cash exchange. However, tax authorities and opportunists participate in these processes, making it seem as if cash flow has truly occurred.

For example, in 1973, AT&T introduced a “dividend reinvestment” program. It was said that this company deeply cared about shareholder interests. Considering the atmosphere in the financial industry, the implementation of such a program was entirely understandable. However, the content of this plan seemed to come straight out of the fairytale “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.”

In 1976, AT&T distributed $2.3 billion in cash dividends to its 2.9 million common shareholders. By the end of that year, a total of 648,000 shareholders (compared to the previous year’s 601,000) reinvested $432 million (compared to the previous year’s $327 million) in additional shares directly issued by the company.

Just for the sake of amusement, let’s assume that all AT&T shareholders participated in this program. If that were the case, the shareholders would not have seen a single penny, while the electric company at least sent them a dividend.

Furthermore, the 2.9 million shareholders were required to pay income tax on the earnings retained by the company, as the retained earnings were renamed “dividends” that year.

Suppose the total amount of “dividends” in 1976 was $2.3 billion. Assuming an average income tax rate of 30% paid by shareholders, they would end up paying approximately $700 million to the tax authorities for this unbelievable plan. Just imagine how delighted the shareholders would be if the board of directors decided to double the dividends.

Government Intervention in Capital Accumulation

It is anticipated that in response to the accumulation issues surrounding real capital, companies will employ various strategies to reduce dividends. However, such measures that divert shareholder benefits alone cannot fully address the problem.

The combined effects of a 7% inflation rate and a 12% return rate will result in companies losing the funds originally intended for investment in real growth.

Similarly, as private companies face slow capital accumulation in an inflationary environment, governments will increasingly seek to intervene in capital to stimulate its flow into the industrial sector. This approach may either fail, as in England, or succeed, as in Japan.

We lack the cultural and historical traditions necessary to form the close relationships between the government, businesses, and labor force, similar to those in Japan. If we are fortunate enough, we can avoid following the path of the United Kingdom, where every department fights for its own share of the cake instead of working together to make the cake bigger.

In summary, as we have witnessed in recent years, we will continue to hear more examples of inadequate investment, stagnation, and the inability of the private sector to meet people’s needs.