Cycles are an inevitable phenomenon in investments. For investors, the most challenging aspect is the difficulty in determining the real-time position within a cycle. Only after it has passed can one truly identify whether it was a peak or a trough. However, investors can utilize historical information to assess current investment opportunities and risks.

Over time, significant changes have occurred in the economic, political, and investment landscapes. Major technological innovations, such as the internet, and challenges like climate change, have evolved in conjunction with typical cycles of economic growth, inflation, and interest rates.

In other words, despite experiencing numerous changes, economic activity and patterns of financial asset returns continue to cycle. In summary, here are some important insights.

What Can We Learn from the Past?📚

The returns that assets bring to investors depend on various factors, with the most important ones being the investment time span and initial valuation. The longer investors are willing to hold investments, the higher the risk-adjusted returns can be.

This point is particularly crucial for stock investors. For instance, stocks purchased at the peak of the 2000 dot-com bubble had the worst 10-year returns in over a century due to excessive initial valuations. Similarly, the Nikkei 225 index of the Japanese stock market is currently about 45% lower than its peak level in 1989. The S&P 500 index didn’t reach its 1929 level until 1955. While these are historically exceptional moments, most can be attributed to valuations.

It is not difficult to understand that, based on risk-adjusted returns, the periods following valuation peaks (1929, 1968, 1999) tend to have very low returns, while the periods following market bottoms (1930, 1973, 2008) with extremely low valuations often have very high returns.

Since 1860, the average annualized total return of US stocks has been around 10%, within holding periods ranging from 1 to 20 years.

For 10-year government bonds, the average return within the same holding period ranges between 5% and 6%. While in the short term, stock returns adjusted for volatility (risk) are often much lower than bonds, investors usually achieve returns by assuming risks in the long run.

Stock markets (and other asset classes) often exhibit cyclic volatility over long periods.

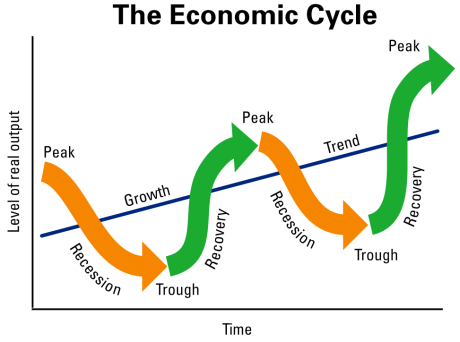

With the maturation of economic cycles, each cycle can usually be divided into four stages, each reflecting different driving factors:

- Desperation stage: In this stage, the market transitions from a peak to a trough, also known as a bear market.

- Hope stage: This stage is a brief period of rebound from the trough through multiple expansions (averaging 10 months in the US and 16 months in Europe). It is a critical phase for investors as it often represents the highest returns within the cycle, typically starting when macro data and corporate profit performance are still weak.

- Growth stage: This is usually the longest-lasting phase (averaging 49 months in the US and 29 months in Europe), where profits begin to increase, driving higher returns.

- Euphoria stage: The final stage of the cycle when investors become increasingly confident, even complacent. Valuations often rise again, surpassing the growth in returns. In the US, this stage typically lasts for about 25 months.

Avoiding bear markets is crucial as stock returns are highly concentrated within the stock market cycle.

The variability of annual returns can be significant. The lowest annualized return for the S&P 500 index after World War II was -26.5% in 1974, while the highest was 52% in 1954. History shows that over time, avoiding the worst months and investing in the best months are equally valuable.

Not all bear markets are the same. From a historical perspective, bear markets can be divided into three categories based on severity and duration: cyclical, event-driven, and structural.

Cyclical and event-driven bear markets generally see price declines of around 30%, while structural bear markets have much larger price declines of about 50%. Event-driven bear markets tend to be the shortest, averaging 7 months; cyclical bear markets last an average of 26 months, while structural bear markets average 3.5 years to recover to their previous peak values.

Bull markets can bring powerful returns. As a rough rule of thumb, in the case of the US, average stock prices in bull markets rise by over 130% within 4 years, with an annualized return rate of approximately 25%. Some bull markets are driven by sustained valuation growth and can be broadly described as long-term bull markets. The post-war prosperity from 1945 to 1968 and the long-term prosperity following the tight monetary policy and end of the Cold War from 1982 to 2000 are prime examples. Bull market trends are less apparent and often more cyclical. They can be classified into the following categories:

- Narrow Trading Range (Low volatility, low returns): The market remains flat, and stock prices stagnate within a narrow trading range with small fluctuations.

- Wide Trading Range (High volatility, low returns): This period (often long) refers to a small overall increase in stock market indices with significant volatility. It involves strong rebounds and pullbacks (even mini-bull and bear markets).

What Can We Learn from the Present?⏲️

Despite the market’s continuous tendency towards cyclical fluctuations, the post-financial crisis cycle differs in many aspects from the past.

On one hand, the economic cycle has been unusually long, especially in the case of the United States, where the current cycle is the longest in over a century. On the other hand, inflation expectations have slowed down, and bond yields have reached historical lows. The long-term bond yields in the UK have hit their lowest levels since 1700, with over $14 trillion in government bonds yielding negative returns. In terms of profit growth and returns, technological innovation has also led to an increasing gap between relative winners and losers. Since the financial crisis, the technology sector has been a major source of profit margins and growth.

Since the financial crisis, the relatively weaker economic growth, significantly low inflation expectations, and the economic backdrop of bond yields mean that investors face scarcity of income and growth (due to policy rates approaching or even going below zero):

Compared to the pre-financial crisis period, the number of high-growth companies has decreased, and overall, the revenue growth rate in the corporate sector has slowed down. These factors combined have led to a chase for yields in both fixed income and credit markets, which is also reflected to a large extent in the performance of growth stocks relative to value stocks.

Whether in the credit market or the stock market, the higher the uncertainty about future growth, the higher the premium for quality. In other words, companies with stronger balance sheets are less sensitive to economic cycles. This situation may persist unless or until economic growth and inflation expectations return to the general levels seen in the pre-financial crisis cycle.

Due to the aforementioned changes and the initiation of quantitative easing, the valuation of financial assets has generally increased, indicating lower future returns.

Zero bond yields do not necessarily benefit stocks. The experiences of Japan and Europe show that lower bond yields increase the required equity risk premium, which is the additional return investors demand for purchasing stocks compared to default-free government bonds.

Zero or negative bond yields can reduce the volatility of cycles and influence the cycle, but at the same time, it makes the stock market more sensitive to long-term growth expectations. If a shock leads to an economic recession, we may see a more significant negative impact on stock valuations than what we witnessed in past cycles.

With bond yields at zero or negative levels, pension funds and insurance companies are susceptible to debt mismatches. This could lead to some institutions taking on excessive risk in pursuit of guaranteed returns, but the decline in yields could also increase the demand for bonds, further pushing down bond yields.

Another structural shift has occurred due to technological innovation. It is estimated that 90% of the world’s data has been generated in the past two years. This rapid transformation has influenced the distribution between relative winners and losers. The largest companies have become even more massive, with the total market value of Amazon, Apple, and Microsoft surpassing the annual GDP of Africa’s 54 countries. Technology stocks dominate the US stock market.

History shows that this situation is not uncommon. Over time, different technological waves have divided industry dominance into different stages, starting from financial stocks (1800 to the 1850s), transportation stocks reflecting the prosperity of railways (1850s to the early 1910s), and energy stocks (1920s to the 1970s).

Since then, except for a brief period before the 2008 financial crisis, technology has consistently held the dominant position. This is evident from the evolution from mainframe computers (IBM becoming the highest-valued stock in the S&P 500 in 1974) to personal computers (Microsoft becoming the highest-valued company in 1998) to Apple (becoming the highest-valued company in 2012).

📖What Can We Expect for the Future?

The future financial cycles are not the focus of this book. However, by observing past and current cycles, we can gain some clues for future expectations.

One of the most consistent observations from past cycles is the importance of valuation.

High valuations often lead to lower future returns, and vice versa. In the post-financial crisis cycle, the level of inflation in product markets was relatively low, while the level of inflation in financial assets was high (resulting in higher returns). This unusual combination was partly caused by the same factor: continuously declining interest rates.

The decline in real interest rate levels can reflect several factors: aging population, excess savings, the impact of technology on pricing, and globalization.

To some extent, this also reflects the aggressive quantitative easing policies adopted by central banks around the world after the financial crisis.

The decline in real yields, coupled with the decline in overall growth rates, has made economic cycles longer than what we have seen in the past.

At the same time, economies, businesses, and investors have become more dependent on the continuation of these current conditions. This suggests that investors will face some unusual challenges in the coming years.

Although the possibility of an economic recession in the short term remains unlikely, there is much less room to lower interest rates in the face of economic shocks, making it more difficult to recover from an economic downturn.

Governments may consider increasing borrowing and fiscal expansion when financing costs are at historically low levels, which becomes increasingly attractive.

However, if such borrowing triggers stronger economic growth, at some point, inflation expectations and interest rates are likely to rise from their current historical lows. As bond yields rise to higher levels, it may trigger financial asset devaluation.

One possible outcome is the recovery of economic activity to the growth pace before the financial crisis.

This will boost people’s confidence in future growth, but at the same time, it may significantly increase long-term interest rates, increase the risk of financial asset devaluation, and potentially lead to painful bear markets in stocks and bonds. Another possible scenario is that economic growth, inflation, and interest rates remain very low, similar to Japan’s situation in recent decades.

Although this may reduce the volatility of financial assets, it is likely to come with lower returns. With the aging population and long-term liabilities formed by healthcare and pension costs, the demand for returns continues to rise, making it harder to achieve the desired returns without taking on greater risks.

Perhaps the biggest challenge will come from climate change and the need for economic decarbonization.

Although efforts in this area are costly, they also provide important opportunities for investment and adjusting the economic structure, making future growth more sustainable.

Technological achievements are beginning to emerge.

In the past 8 years, the cost of wind power has decreased by 65%, solar power by 85%, and batteries by 70%. In the next 15 years, new technologies will not only provide renewable energy at prices comparable to fossil fuel generation but also offer low-cost backup and storage systems, enabling power systems relying on intermittent renewable energy to operate at 80% to 90%.

In the long run, even with the volatility caused by cycles, investments can yield high profits. Different assets often perform best at different times, and returns depend on the investor’s risk tolerance.

Especially for stock investors, history has shown that if they can hold their investments for at least 5 years, particularly if they can identify signs of bubbles and cycle changes, investors can truly enjoy the benefits of long-term returns.